THIS WEEK IN ARMENIAN HISTORY

Prepared by the Armenian National Education Committee (ANEC)

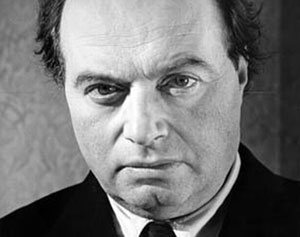

Death of General Antranig (August 31, 1927)

From Armenia to Argentina, there are statues, memorials, streets, metro stations, even a highway section (in Connecticut) which remember General Antranig’s name. Perhaps the most recognizable Armenian hero of the twentieth century, he was highlighted in 1920 by The Literary Digest as "Armenia’s Robin Hood, Garibaldi, and Washington, all in one. He is the ideal patriot of whom broadside ballads are published, and whose name inspires songs sung by the Armenian at his workbench, by the Armenian housewife at her tasks, by their children at play.”

Antranig Ozanian was born on February 25, 1865, in the city of Shabin-Karahisar, in the vilayet of Trebizonda. He was the son of a carpenter, Toros; his mother Maria m died when he was one-year-old. He married at the age of 17, but his wife died a year later, after giving birth to their son, who also died days later

m died when he was one-year-old. He married at the age of 17, but his wife died a year later, after giving birth to their son, who also died days later

He was 23 when he joined the revolutionary groups of the Social Democratic Hunchakian Party (founded in 1887), and became a party member in 1891. In 1894 Antranig left the Hunchakian Party and joined the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (founded in 1890). The next year he met the fedayee commander Aghpiur Serop and joined his group. After Serop’s death in 1899, Antranig became the leader of fedayee groups of Vasburagan and Daron in Western Armenia. His first mission was to capture and kill Beshara Khalil, a Kurdish soldier of the Ottoman Hamidiye regiments and tribal chief who had murdered Aghpiur Serop and was notorious for his atrocities against the Armenian population.

Antranig’s most famous battles were the battle of the Monastery of Holy Apostles in Mush (1901) and the second resistance of Sasun in 1904. In November 1901, Antranig barricaded himself in the Monastery of Holy Apostles in Mush with 30 fedayees, including the famed Kevork Chavush, and some ten peasants. The well-fortified monastery was besieged by five Turkish battalions with a total of 1,200 men. After a nineteen-day resistance and causing substantial losses to the Turkish army, the group was able to leave the monastery and flee in small groups. Antranig gained legendary stature among Armenians after breaking through the siege. In 1924 he would write in his memoirs that “it was necessary to show to the Turkish and Kurdish peoples that an Armenian can take a gun, that an Armenian heart can fight and protect his rights.”

He participated in the second insurrection of Sasun in 1904. He was pressed by Armenian leaders to allow temporary peace in the region. He moved to the Caucasus through Iran and then traveled to Europe, where he was engaged in advocacy in support of the national liberation struggle. In 1906 he published a book of military tactics in Geneva. In 1907 he settled in Bulgaria. During the fourth Congress of the A.R.F. (Vienna, 1907), Antranig announced his decision to leave the party due to his disagreement about the establishment of cooperation with the Young Turks.

He participated in the First Balkan War of 1912-1913 within the Bulgarian army, together with Karekin Nzhteh and a detachment of 273 Armenian volunteers. Antranig was honored with the Order of Bravery for his heroic participation in the war.

During World War I, Antranig returned to the ranks of the A.R.F. and participated in the Caucasus Campaign as head of the first Armenian volunteer battalion, which helped lift the siege of Van on May 6, 1915. He participated in twenty different offensives where he gained fame due to his courage and his tactics to defeat the Ottoman forces. The Russian authorities made him a Major General in 1918 and decorated him five times for bravery.

After the disbandment of the six volunteer battalions in 1916, Antranig resigned his commission and departed from the front. He left the ranks of the A.R.F. for the second time in 1917 and organized the First Congress of Western Armenians; he also published the newspaper Hayasdan in Tiflis in 1917-1918, with writer Vahan Totovents as its editor.

After the Russian army left the Caucasus following the Revolution, Armenian forces were created in a rush to try to fill the vacuum against the Turkish offense. In March-April 1918, Antranig was the head of a provisional government created in the areas of Western Armenia formerly occupied by the Russians. His military leadership allowed the Armenian surviving population to escape to Eastern Armenia.

After the foundation of the Republic of Armenia in May 1918, Antranig fought along volunteer units against the Ottoman army. In July of the same year, he arrived in Zankuezur, in the south, to participate in the interethnic warfare between Armenians and the local Turkish population. He also tried several times to seize Shushi, the most important city of Karabagh, but was prevented by British troops in the area.

In April 1919, Antranig arrived in Holy Etchmiadzin. His 5,000-strong division had dwindled to 1,350 soldiers. As a result of disagreements with the government of the Republic and British diplomatic machinations in the Caucasus, Antranig disbanded his division and handed over his belongings and weapons to Kevork V, Catholicos of All Armenians. In late 1919 he led a delegation to the United States to lobby in support of an American mandate. He was saluted as “the George Washington of Armenians.”

He married again in Paris in 1922, with Boghos Nubar Pasha as best man. Antranig and his wife, Nevart Kurkjian, settled in Fresno, California, where a young William Saroyan met him and later described the meeting in his short story “Antranig of Armenia” (Inhale and Exhale, 1936). He passed away near Chico, in northern California, on August 31, 1927, of a heart attack. His remains were moved to the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris in early 1928. They were set to be buried in Armenia, according to his desire, but Soviet authorities refused entry. His body was eventually returned to Armenia in 2000 and was reburied at the Yeraplur Military Cemetery.

Read Full Post »

You must be logged in to post a comment.